One of the core things that I value the most about watches and a large part as to why I got into it in the first place largely stemmed from the idea that watches are lasting objects and in general, are resistant to the passage of time. Sure, fleeting fashion trends do find their way into watch design, but if we are talking purely about the mechanism of a watch, it is certainly something built to last generations and is the antithesis of mainstream technology – impervious to being obsolete. Despite losing a few seconds here and there, the superiority of quartz and of course the advent of time telling on our smart phones, we have persisted with wearing mechanical wristwatches, why? A watch made in the 40’s is no different fundamentally to a watch that is made today and that is something very telling. We will always need to tell the time, and a mechanical watch will always do that for you in a very faithful and endearing way. Furthermore, a mechanical watch is perhaps the only appropriate object that can be passed down that both has the ability to possess functionality through its myriad of complications and sentimentality through its ability to stand the test of time. This is the point of my article today as I write about the most important watch that I own – the Patek Philippe 3940G Perpetual Calendar Moonphase.

Firstly, a little about the watch. The Patek Philippe Ref. 3940 is considered to be one of the most important pieces in Patek’s modern history, as it was the first highly complicated serially produced timepiece with a perpetual calendar alongside the perpetual calendar chronograph Ref. 3970. When looked at in context, the 3940 is significant in the sense that when it was released in 1985, Switzerland was in turmoil. An economic crisis in the Swiss watchmaking industry set upon by the Quartz crisis (or revolution depending on how you look at it), mechanical watches, a significant driver of the Swiss economy, had on paper become redundant. As an indicator of the drastic times and the effects felt, the number of people working in the Swiss watch industry dwindled from 90,000 to around 28,000 in the space of 18 years.

Firstly, a little about the watch. The Patek Philippe Ref. 3940 is considered to be one of the most important pieces in Patek’s modern history, as it was the first highly complicated serially produced timepiece with a perpetual calendar alongside the perpetual calendar chronograph Ref. 3970. When looked at in context, the 3940 is significant in the sense that when it was released in 1985, Switzerland was in turmoil. An economic crisis in the Swiss watchmaking industry set upon by the Quartz crisis (or revolution depending on how you look at it), mechanical watches, a significant driver of the Swiss economy, had on paper become redundant. As an indicator of the drastic times and the effects felt, the number of people working in the Swiss watch industry dwindled from 90,000 to around 28,000 in the space of 18 years.

During this time of uncertainty, Patek Philippe, then headed by Philippe Stern, surprisingly released the 3940 and 3970 as a pair. Big Swiss companies were not making complicated pieces at this time as the decline in the industry meant that there was no spare money for innovative investment but instead only enough to consolidate whatever market share they had left. To release a perpetual calendar and perpetual calendar chronograph at the same time, was certainly a bold move by Patek and the timing could not have been greater as the tide was slowly turning with people realising the value of mechanical watches. This is partly because looking at a mechanical watch and its movement is a very relatable experience, where you can see how it works, how it is all connected unlike a quartz watch that is powered by an incomprehensible chipboard. Perhaps it has something to do with a universal appreciation we have for craftsmanship as a whole, but whatever it was, this watch is a significant bedrock as to how far Patek has come today despite the adversities it faced. It is no coincidence that Philippe Stern himself, who despite being in the position to wear any and as many Patek Philippe watches he wished, chose to wear a 3940 every day.

During this time of uncertainty, Patek Philippe, then headed by Philippe Stern, surprisingly released the 3940 and 3970 as a pair. Big Swiss companies were not making complicated pieces at this time as the decline in the industry meant that there was no spare money for innovative investment but instead only enough to consolidate whatever market share they had left. To release a perpetual calendar and perpetual calendar chronograph at the same time, was certainly a bold move by Patek and the timing could not have been greater as the tide was slowly turning with people realising the value of mechanical watches. This is partly because looking at a mechanical watch and its movement is a very relatable experience, where you can see how it works, how it is all connected unlike a quartz watch that is powered by an incomprehensible chipboard. Perhaps it has something to do with a universal appreciation we have for craftsmanship as a whole, but whatever it was, this watch is a significant bedrock as to how far Patek has come today despite the adversities it faced. It is no coincidence that Philippe Stern himself, who despite being in the position to wear any and as many Patek Philippe watches he wished, chose to wear a 3940 every day.

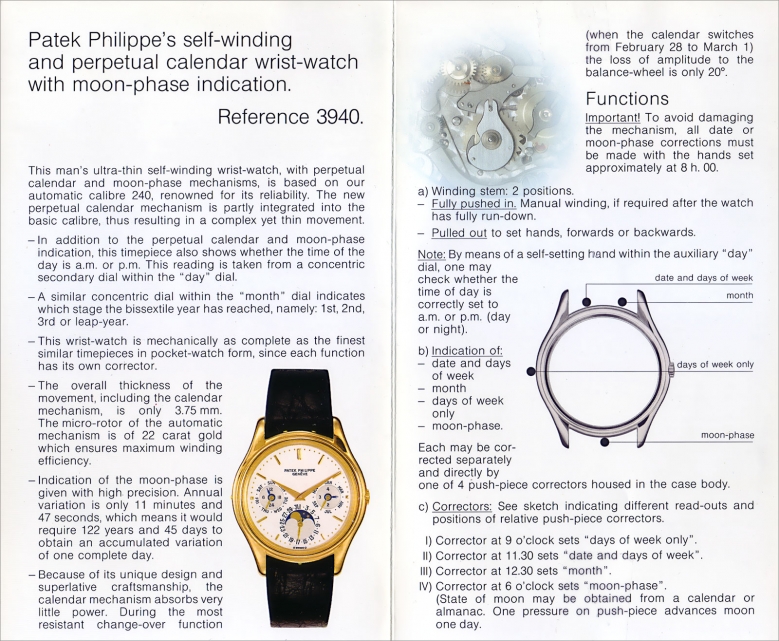

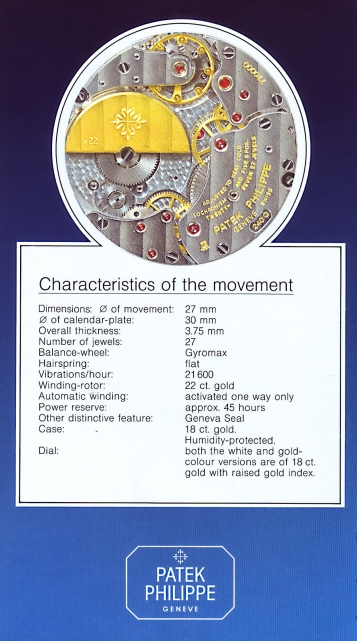

Stepping back from the contextual significance of the 3940, the watch in itself is a marvel both in its design and movement. Housing the fantastically finished in-house perpetual calendar calibre 240 Q, one of its defining aspects is the integrated off centre micro rotor, allowing this incredibly complicated watch to come in at an unbelievably slim 9mm. In order to ensure that a rotor that small could power the watch, it was made in 22k gold, with the extra weight providing more force to wind the watch.

Stepping back from the contextual significance of the 3940, the watch in itself is a marvel both in its design and movement. Housing the fantastically finished in-house perpetual calendar calibre 240 Q, one of its defining aspects is the integrated off centre micro rotor, allowing this incredibly complicated watch to come in at an unbelievably slim 9mm. In order to ensure that a rotor that small could power the watch, it was made in 22k gold, with the extra weight providing more force to wind the watch.

Making a perpetual calendar is no easy task, with 275 different parts and as testament to this, at the time it was released, there were only two people in the manufacture allowed to make watches this complicated. Sure, a perpetual calendar does not enjoy the same status as a chronograph, despite being more difficult to manufacture, as it lacks the tactile experience. But for a watch to have a memory of 4 years, accounting for the days in every month including February and the leap year, involves a large measure of skill. Add a moonphase and 24-hour clock on top and you start to understand the complexity of this.

Making a perpetual calendar is no easy task, with 275 different parts and as testament to this, at the time it was released, there were only two people in the manufacture allowed to make watches this complicated. Sure, a perpetual calendar does not enjoy the same status as a chronograph, despite being more difficult to manufacture, as it lacks the tactile experience. But for a watch to have a memory of 4 years, accounting for the days in every month including February and the leap year, involves a large measure of skill. Add a moonphase and 24-hour clock on top and you start to understand the complexity of this.

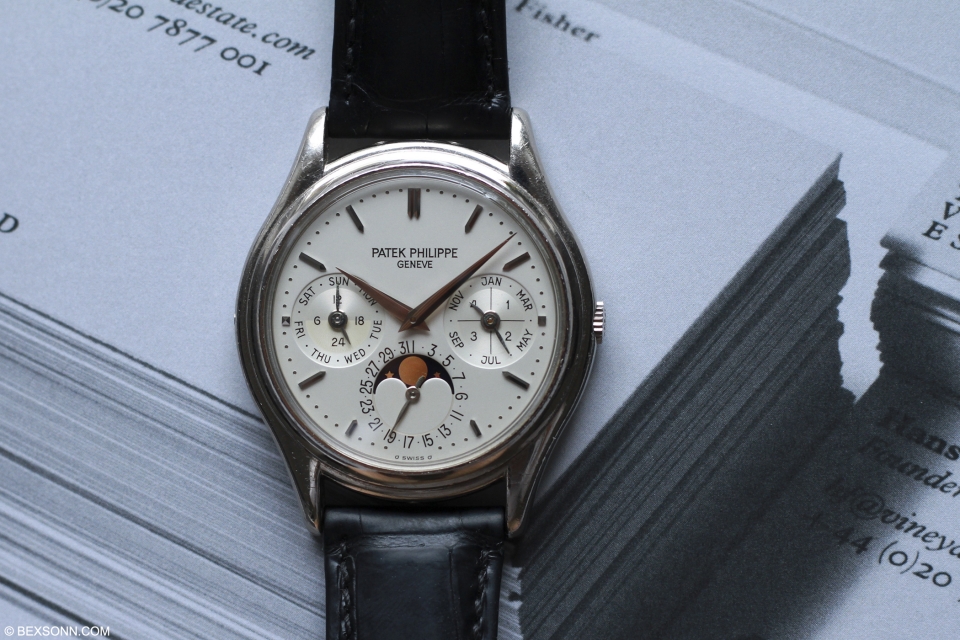

The aesthetics of the watch is an exercise in restraint, a timeless design combining the need for legibility with a beautiful symmetry of sub dials. It has a white opaline dial with white gold applied index markers and dauphine hands. Each sub dial provides two sets of information, with the 3 o’clock sub dial showing the leap year indicator and the day of the week, the 6 o’clock sub dial showing the enamel moonphase and the day of the month, and finally the 9 o’clock sub dial showing the 24-hour clock and the month. The sub dials are systemised within concentric circles and in an obvious hierarchy, with the day, month and date on the outer track of the sub dial, with the less important leap year indicator, moon phase and 24-hour clock inside it. A cool little quirk of these early 3940’s is in the 24-hour subsidiary dial. In what looks to be discolouration, the orange tint of the bottom half is actually a subtle indicator to show that it is night-time.

The aesthetics of the watch is an exercise in restraint, a timeless design combining the need for legibility with a beautiful symmetry of sub dials. It has a white opaline dial with white gold applied index markers and dauphine hands. Each sub dial provides two sets of information, with the 3 o’clock sub dial showing the leap year indicator and the day of the week, the 6 o’clock sub dial showing the enamel moonphase and the day of the month, and finally the 9 o’clock sub dial showing the 24-hour clock and the month. The sub dials are systemised within concentric circles and in an obvious hierarchy, with the day, month and date on the outer track of the sub dial, with the less important leap year indicator, moon phase and 24-hour clock inside it. A cool little quirk of these early 3940’s is in the 24-hour subsidiary dial. In what looks to be discolouration, the orange tint of the bottom half is actually a subtle indicator to show that it is night-time.

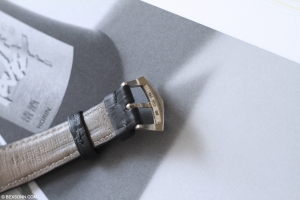

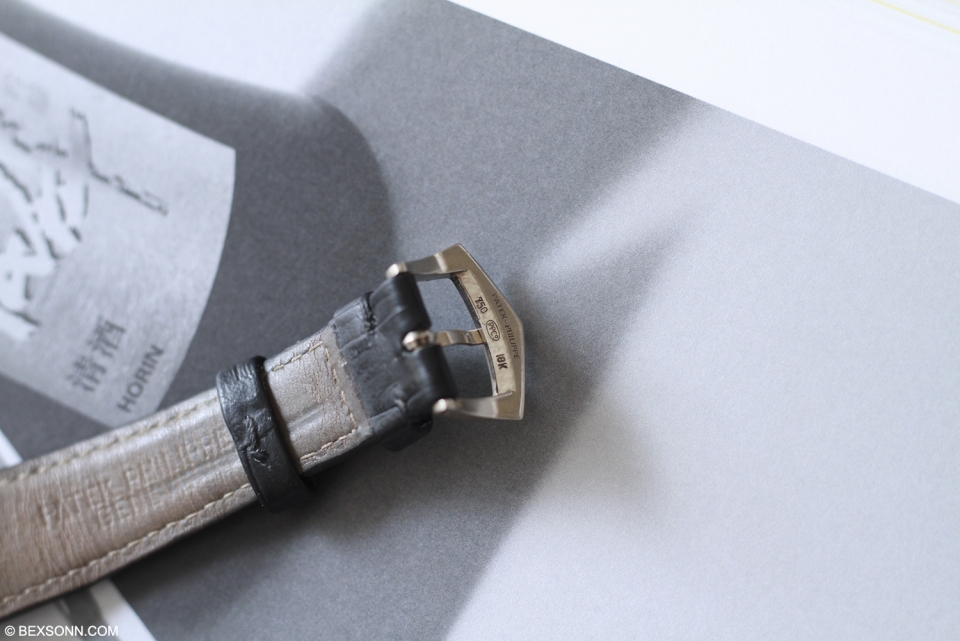

The 36mm curved case sits proportionately elegant on the wrist and its ultra slim profile completes what is perhaps one of the most understated and elegant timepieces. My watch came with the angular tang buckle, which I much prefer than the more ornamental Calatrava deployant clasp. The 3940 interestingly was offered with both a sapphire caseback and a solid gold case back – after many early clients who bought the first series, which were only offered with a solid caseback, requested for sapphire ones.

The 36mm curved case sits proportionately elegant on the wrist and its ultra slim profile completes what is perhaps one of the most understated and elegant timepieces. My watch came with the angular tang buckle, which I much prefer than the more ornamental Calatrava deployant clasp. The 3940 interestingly was offered with both a sapphire caseback and a solid gold case back – after many early clients who bought the first series, which were only offered with a solid caseback, requested for sapphire ones.

While it is true that the 3940 does not shout out, it is for this reason I love the watch so much. This idea that you can wear this watch with barely anyone noticing, but you yourself knowing you have something truly special on is very, very appealing to me. There is a real purity to the design where perfect symmetry was achieved, balancing both undeniable elegant aesthetics with a fantastic movement. It is no wonder this watch was in production from 1985-2006, one of the longest run in Patek’s history.

While it is true that the 3940 does not shout out, it is for this reason I love the watch so much. This idea that you can wear this watch with barely anyone noticing, but you yourself knowing you have something truly special on is very, very appealing to me. There is a real purity to the design where perfect symmetry was achieved, balancing both undeniable elegant aesthetics with a fantastic movement. It is no wonder this watch was in production from 1985-2006, one of the longest run in Patek’s history.

A short note on the 3940’s replacement, the 5140, in my opinion simply cannot compare. As a testament to the 3940, Patek chose not to touch the 240Q movement and even with a change in reference, the movement remained exactly the same. Design wise though, with a larger, bolder logo and fonts, not to mention the weird squished ’27’ and ‘5’ on the date wheel as a consequence, really seems like a contradiction to the understated style they achieved with its predecessor. Proportionality is one of nuance and subtlety, and with a small increase of 1 mm in the case size and an outward facing bezel, the charm that made the 3940 such a beloved watch, sadly, I feel has largely been lost. Moreover, priced at least £20,000 more than a 3940, one can see how the 3940 in many experts’ eyes, is viewed today as one of the most undervalued watches out there. Sure it is by no means a rare watch, but I feel with due time, a market correction for these pieces are in order as it simply does not make sense when comparing to a 5140.

A short note on the 3940’s replacement, the 5140, in my opinion simply cannot compare. As a testament to the 3940, Patek chose not to touch the 240Q movement and even with a change in reference, the movement remained exactly the same. Design wise though, with a larger, bolder logo and fonts, not to mention the weird squished ’27’ and ‘5’ on the date wheel as a consequence, really seems like a contradiction to the understated style they achieved with its predecessor. Proportionality is one of nuance and subtlety, and with a small increase of 1 mm in the case size and an outward facing bezel, the charm that made the 3940 such a beloved watch, sadly, I feel has largely been lost. Moreover, priced at least £20,000 more than a 3940, one can see how the 3940 in many experts’ eyes, is viewed today as one of the most undervalued watches out there. Sure it is by no means a rare watch, but I feel with due time, a market correction for these pieces are in order as it simply does not make sense when comparing to a 5140.

Coming full circle, you may be wondering how this watch of mine ties in to my statements made earlier in the article. Everything I said about the 3940 is very fascinating to me and draws me to the watch, but it is not why I cherish it the most. You see, with watches for me and I’m sure for many, it is about the sentimentality of the piece and how it came about. For instance, there is a reason why military watches are so collectible, it is because they have a story to tell. Sure, some stories may be more personal than others, but at the end of the day, we all have phones that tell us the time – we don’t need to wear anything on our wrists. For me, the 3940 is significant because it was the watch my father bought when I was born and wore for many years before gifting it to me. I suppose the folks at Patek are writhing in their seats that someone actually followed their slogan of ‘you never really own a Patek, you merely look after it for the next generation.’ This watch as you can see in the images, is full of scratches and dinks, which I never intend to polish out. Its worn condition is representative of my father who wore it before me with the watch as a vessel of his adversities and experiences. I look up to what he has been through and achieved and it’s perfectly summed up in 36mm. I certainly intend to carry this on and pass it down and it is for that reason I have developed such a strong love for mechanical watches.

Coming full circle, you may be wondering how this watch of mine ties in to my statements made earlier in the article. Everything I said about the 3940 is very fascinating to me and draws me to the watch, but it is not why I cherish it the most. You see, with watches for me and I’m sure for many, it is about the sentimentality of the piece and how it came about. For instance, there is a reason why military watches are so collectible, it is because they have a story to tell. Sure, some stories may be more personal than others, but at the end of the day, we all have phones that tell us the time – we don’t need to wear anything on our wrists. For me, the 3940 is significant because it was the watch my father bought when I was born and wore for many years before gifting it to me. I suppose the folks at Patek are writhing in their seats that someone actually followed their slogan of ‘you never really own a Patek, you merely look after it for the next generation.’ This watch as you can see in the images, is full of scratches and dinks, which I never intend to polish out. Its worn condition is representative of my father who wore it before me with the watch as a vessel of his adversities and experiences. I look up to what he has been through and achieved and it’s perfectly summed up in 36mm. I certainly intend to carry this on and pass it down and it is for that reason I have developed such a strong love for mechanical watches.

So with that, Happy belated Father’s Day Pa.